MEMBER SPOTLIGHT Q&A: DEAN EILERTSON

Dean Eilertson (middle) has spent 35 years helping to design and build worlds for the motion picture industry as an IATSE 891 Props Department member. A master of his craft, Dean’s credits include ‘Night At The Museum’, ‘I, Robot’, and ‘Shōgun’, for which he won a Property Masters Guild MacGuffin Award in 2025. With plans to soon retire, he reflects on highlights from his incredible career and shares advice for those interested in working in motion picture production in BC.

(Photo left to right: MacGuffin Award presenter Writer and Director Matthew Weiner, 891 Props member Dean Eilertson, and 891 Props member Paul Wagner.)

1. WHAT DREW YOU INTO A CAREER IN THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY?

I come from a Fine Arts background — attended the Alberta College of Art in Calgary and the Master of Fine Arts program at Concordia in Montreal. My mindset was I was going to be an artist. I was getting grants and doing exhibitions, but it was not paying the bills. I was sharing an apartment with an actor attending theatre school and they said that since I can conceptualise and build things I should be a scenic carpenter. I found this guy who had a small shop building scenery for TV commercials. I didn't have a clue what carpentry was, but I got a job there, 5 bucks an hour, sweeping the floor, cutting materials, and for the next 10 years, I was a scenic carpenter in Montreal.

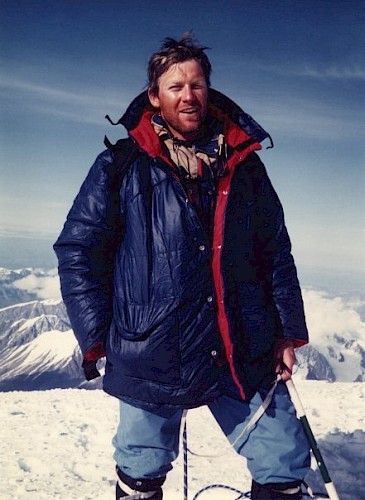

After that I had my own scenic shop for awhile and was a construction coordinator. I knew there was better motion picture production work going on in the West Coast and a friend at a small production company got a contract to produce a show in Vancouver and so I got into the BC film industry early. I worked on productions like MacGyver and Poltergeist, but by 1989 I was working so hard that it was a burnout period for me. I decided to go back to school and applied to UBC’s graduate program in architecture, but people kept telling me that with my skills I could be an art director or set designer, and that there's lots of options in film. Eventually I realised how much I really loved what I was doing in film so I went back. I ended up working on K2. I have a climbing background, and I was being paid to climb mountains every day! It was great.

Dean on location in BC for the filming of ‘K2’.

Thinking back, I really knew I wanted to be part of this industry when one night coming home from a gallery opening in Montreal, I came across this line of people down the block and around the corner to the other end of the block. They were waiting in the rain to go to a movie. That wasn’t happening at the art galleries. It hit me the power of film as an artform. I still get choked up about it when I talk about it, but that was my mindset — I want to be part of that.

2. WHAT ARE SOME ANECDOTES FROM YOUR CAREER THAT ILLUSTRATE THE CHALLENGES AND JOY OF THE KIND OF WORK YOU DO?

During filming for the Night At The Museum there were constant changes with the script. Ben Stiller was running around carrying this heavy tablet and they kept trying to find excuses to put a bag on him so he could lose the tablet because Ben didn’t want to be carrying this heavy thing around the whole time. We got a moon rock sample bag because one scene is in the space part of the museum. Then we were going into the Egyptian exhibit of the museum so now we had to find something that fits that. We’re hunting down all these different kinds of bags for different scenes shot in different museum exhibits. Then the costume designer says, ‘Hey, I've got some cut offs from the costume we made for one of the Egyptian characters. I'll go get those for you and some leather and you can use that for a bag!’

Talk to any Props person and you’ll learn we're always going through that sort of scramble. You can't do paint by numbers. You have to dive into the script and the characters if you want to make a mark. It requires thinking deeper. I've been accused of being the method Property Master, but I've got to understand the story deeply to do my job well. One day it really hit me that I am part of a service industry and being professional is so important. For these incredible actors we get to work with, they're looking for somebody in the Props Department to have done the research and to help them with their character, because we on set, we are the resident experts of whatever the subject matter is of what we’re filming.

Dean’s props being put to the test on the set of ‘X-Men: The Last Stand’.

The Andromeda Strain was another prime example. They have this space craft orbiting past Pluto, and going into the tail end of comets, and getting samples of space dust. It comes back to Earth, crashes in the desert, and these two kids find it. They decide to pry it open, and Andromeda is released and starts killing everything. The design for the space craft I was given by the Art Department reflected a little sphere with a snorkel coming out, but I did my own research and find out there's actually been space missions like this, and they use this stuff called aerogel, which is the lightest human-made material in the world. They put it in little mesh screens shaped like paddles that come out of the space craft as it flies through the tail of a comet, and this gel captures particles. So that is how we ended up designing it. To me it had to be done that way.

Dean on the set of ‘The Andromeda Strain’.

3. CONGRATULATIONS ON WINNING A MACGUFFIN AWARD THIS YEAR FOR YOUR WORK ON SHOGUN! WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO YOU TO RECEIVE THIS AWARD?

I'm one of the founding members of Property Masters Guild (PMG). Among Props people there's always been frustration over the lack of inclusion and recognition for our work. On The Revenant, for example, the production designer and the set decorator and the art directors were all nominated for an Oscar, but there's no category for Props at the Oscars or the Emmys. It's only the second year that the MacGuffin Awards have been handed out, and these awards have been in the works for years.

People from all over the world were at the MacGuffin Awards ceremony, which took place in the Paramount Studios Theatre on the Saturday night before the Emmys. It's so international, and the great thing is you're being nominated by your peers. Your peers are voting on who's going to win. I’ve made so many friends from England, Italy, Germany, Australia, all over the world, because we are small in terms of the numbers you see in our departments, so Props people really understand and respect and appreciate each other’s work.

Our Local this year brought home two MacGuffin Awards — Dean Goodine for the feature film Heretic and then me for Shōgun. To go up on stage and look out at a theatre full of Props people and accept an award, I almost lost it at one point. I had to turn and sort of talk away from the mic for a moment. I let people know I’m from Vancouver, I'm from IATSE 891, and I've been doing this work for 35 years. The career that I've had has been amazing. Being on that stage was emotional for sure.

4. WHAT WAS IT LIKE BUILDING THE WORLD OF ‘SHOGUN’ AND WHAT PROPS WERE YOU MOST EXCITED ABOUT?

Shōgun was beyond anything I'd ever done before in terms of scale. We’re recreating 1600 Japan. There's been civil war for 250 years. There’s a level of destruction to keep in mind for the tone to everything. It couldn’t be brand new and shiny. We hired Tomo, a buyer out of Japan who had done Pachinko. We’d work on Zoom breaking down each episode, and I'd highlight the stuff I needed to talk to him about, and that's how we’d set out our buying week.

Matchlock rifle prop used for ‘Shōgun’.

The level of detail for each character involves so many layers. For samurai, you have to source matchlock rifles, the traditional swords naginata, yumi bows, arrows, and pouches for the powder for the guns. You also need to source these little pens that they would carry with a little tiny calligraphy brush inside with a bowl that holds a wad of cotton soaked with ink, so the ink doesn't drip out all over the place. They’d use the calligraphy brush and wet it into the cotton to write their messages or orders in the field. We did a lot of research and had a historian we’d run things by. It ended up becoming a committee of people to approve things for look and feel before it went to camera.

I remember this important meal where Lord Toranaga and his brother meet and try to make peace. They haven't talked in years and there's 28 people in the room. Over four days we shot this food scene with a kitchen set up 500 feet away and it was pouring rain during an atmospheric river.

We hired Yutaka Yamamoto, a master chef from Japan. He's retired and lives in BC now. He was willing to take it on. He did his research for the plating and the types of food that would have been served, with two food stylists to help onset. We were ordering food out of Japan, because their fish are only a certain size, whereas in the markets here the fish are too big. We needed crayfish, because that’s what they have in Japan, but here we have lobsters with claws. We were picking up food at the airport and taking it to our master chef in this whole kitchen built for him to prepare food out of. It was quite the operation.

Another story from Shōgun, and this hit me really hard, was we had to get saddles for the samurai. Tomo got in touch with me from a place up past Fukushima at some house belonging to a guy who collects antiques. We were buying through the night, and they had saddles, stirrups, the bits, everything. We get these saddles and start using them in filming and one comes back from set that needed fixing. Well, underneath there was a carving and inscription on the saddle, so I had it translated, and it read: ‘March, Lucky Day, 1634. Name of the maker.’ I'm going like, ‘Oh my God, we are using real antiques from the 1600s on Shōgun!’ It was staggering.

Michael Williamson, the sound recorder on Shōgun, won an Emmy Award and he gave a shoutout to the Props Department and said that he wanted to thank me, Dean Eilertson. I'm thinking, ‘Why would he do that?’ He explained that the Sound Department had set out to record everything live and that it helped them do their job that the Props Department provided real stuff from the period because it transported everyone there.

That was something I've never even thought about or occurred to me in my entire career — that we were doing something that the Sound Department could use and be inspired by. It was the real stuff. There was no pretending.

5. YOU HAVE BEEN A MEMBER OF IATSE 891 FOR 35 YEARS. WHAT DO YOU VALUE MOST ABOUT BEING PART OF A UNIONIZED FILM COMMUNITY?

I've always strongly felt that 891 is a professional union made up of skilled and trained people, and I've really upheld that part of it. Vancouver is very powerful in our industry, especially in the world of scenic construction and special effects, and also what we have within our membership is creative departments, for example, 14 Emmy Awards and Creative Awards for Shōgun!

I remember working on Mission Impossible and we were filming in downtown Vancouver by the Convention Centre, and our trucks were on the street, and the rigging electrics team with all their cable showed up, and the circus was being set up. We basically descended into downtown, and I just watched in awe as these people worked into the night and did their jobs so well. It was so fascinating.

Our cable trucks used in the film industry here in Vancouver are so unique to North America because the earliest workers in our industry came from the fishing industry, and those cable rollers on the back of those trucks are the same system they used to roll out fishing nets. With that equipment, you can put out three kilometres of cable in minutes. It’s pretty neat stuff. Our film crews and technicians are just so good at what we do. Vancouver is really like no other city in our industry.

6. WHAT ARE YOUR HOPES FOR THE FUTURE OF THE INDUSTRY?

What we as the creative side of 891 could benefit from is getting more support. Within the Props Department, there is a problem with perception on the side of management that Props is still a three-person department. Those days are over. We need to start establishing new positions with good pay. On the last few shows I worked on I had two on-set first assistants. Why? Because the shows are so big and so complicated now. One person can't be on set dealing with everything that's coming at them on any given day without some kind of time to prep. On Shōgun, Props was a full-time 22-person department. I was blown away by the amount of support I got from Erin Smith, the producer, and Phil A. Pacaud, the production manager. They'd already cut their teeth on other big shows and understood and appreciated what we were going to need. Props had to build 24 traditional Japanese boats, for example. We got the support for it.

The other thing I want to mention is the importance of training the next generation of crew. There’s a lot of people with a wealth of knowledge that will be retiring. We had an intern with us on Tron. It is so important to have programs like these. It shows the importance of on-set experience. There are many levels of training that you're never going to get in a classroom. When I’ve helped train people, I show them how to do a script breakdown, a budget, and design, but also things like when to pay more for an important prop versus other ways to do things. Why am I taking it to this builder in town and not the other builder? Is it because of price or quality? Not every prop needs to be a $10,000 prop, but when it needs to be good, it needs to be really good. I take who I’m training to the shop where something's being built, to hear the conversations about tone and colours and repair kits that come with the props. Then we go to the Stunt Department and say, ‘Here. Let's see if the props are going to stand up to what you're putting them through.’ That gives us time to make changes. Then finally, we see how it's all applied on set. You have to give somebody that oversight on a project to give them a chance.

7. WHAT ADVICE WOULD YOU GIVE PEOPLE LAUNCHING A CAREER IN MOTION PICTURE PRODUCTION IN BC?

The biggest piece of advice I’d give if you want to work in Vancouver is don't pigeonhole yourself. People end up doing five seasons of a show. They come out after five years, and people have forgotten who they are. Instead, do the pilot and move on. You don't want a reputation in town that you only do a certain kind of thing. Try different things.

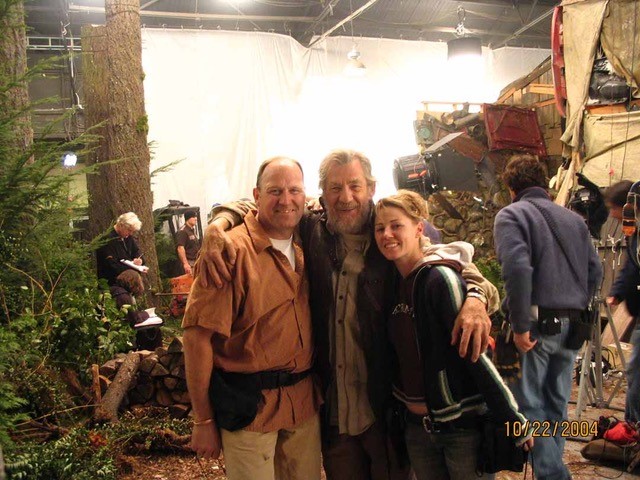

Dean (left) on the set of ‘Neverwas’ with actor Sir Ian McKellan (middle) and 891 Props Department member Michelle Hendriksen (right).

People often ask me: what is your favourite movie you ever worked on? I always answer Neverwas. No one's ever heard of it. No one's ever seen it. It was small budget film, but the cast included Aaron Eckhart, Brittany Murphy, Sir Ian McKellen, and Nick Nolte. All that talent. It was just crazy. They were just doing it because they loved the script. It was such a memorable project.

My other piece of advice is if you want to be a technician, go to BCIT and learn a trade. Whether it's electronics, robotics, welding — any trade that you could add to your resume is something you can use in your work. In Props, we work with the Set Dec Department. We have to be able to read drawings. There will be conversations with construction coordinators. Anything that helps you prepare for that is useful.

Also, the way I’ve always approached the job is to take more than my Fine Arts background and apply all the different things and experiences I’ve had. I spent five years on a Canadian luge team, for example, and was trained to think in a way that meant every day is a race day. That’s how I approached my work.

Interview and editing by 891 Copywriter Claudia Goodine.

Thank you to Dean Eilertson for sharing his story and insights. This Q&A has been edited for length.

Help shine a light on other 891 artists and technicians making BC’s motion picture community a great place to work. Email spotlight suggestions to communications@iatse.com. Read more 891 Member Spotlights here!