SPOTLIGHT: DOREEN MANUEL ON THE ART OF INDIGENOUS COSTUME DESIGN

In honour of Indigenous Peoples Day on June 21st, we spotlight Doreen Manuel — an Indigenous (Secwepemc/Ktunaxa) artist and educator with a passion for advancing authentic representation and inclusion of Indigenous peoples in film. Doreen incorporates Indigenous traditional teachings into contemporary curriculum in her current role as the Director of the Bosa Centre for Film & Animation and Inclusive Community Projects at Capilano University. She is passionate about mentoring and building pathways for the next generation of Indigenous filmmakers. In February 2024, she and Carmen Thompson led an Indigenous Costume Design Workshop for 891 members, with discussions underway to offer similar workshops for other 891 departments in the future. In this Spotlight, Doreen shares insights into what inspires her work, her vision for the future of film in BC, and how the industry can open doors for more collaborative relationships with Indigenous peoples on whose unceded lands our community creates motion picture magic on.

“IATSE 891 and its members acknowledge that we gather upon the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. We offer this acknowledgement as a declaration of our intent for respectful conduct on this land and our commitment to adopting reconciliation as our collective responsibility. ” Watch the full IATSE 891 Equity Statement video here.

Doreen Manuel learned beading from her grandmother. She remembers being told to sit and bead until the hand on the clock showed 30 minutes had gone by. After a while, she’d notice the clock would disappear from the wall. Her grandmother would hide it to stretch out the time.

“Sometimes I'd be there, I think for hours and hours, beading,” she says. “One of the things it taught me was patience, because it doesn't just teach you the art form, it teaches you other things like diligence and determination.”

Today, Doreen describes her hands as efficient as sewing machines. She uses them to make stunning large pieces of art and clothing. This scale of beadwork, she says, is rare these days because of the stamina and skill required that can only come from years and years of focused practice.

“There’s a solid beaded wolf vest, for example, in my collection. That's what I'm talking about by large pieces,” she says. “When I bead now, I do needle beading and I don't even have to look at the beads. I can feel how many beads there are just with my fingers.”

Doreen is known not only for her beautiful Indigenous artwork and clothing, but for being a passionate educator and advocate for fellow Indigenous peoples. With over 19 years of experience in the film industry, she’s passionate about mentoring and building pathways for the next generation of Indigenous filmmakers and decolonizing portrayal of Indigenous peoples in film.

One of the ways she has been doing that is by giving workshops featuring her collection of hundreds of Indigenous clothing items that showcase regional differences in artwork and culture. In February, Doreen teamed up with Carmen Thompson to lead such a workshop for IATSE 891 members.

The Indigenous Costume Design Workshop gave Union members the opportunity to see a collection Doreen has been building for the last 50 years. The collection features hundreds of contemporary and traditional Indigenous items that date back to the early 1900s. Some items were passed down between generations in her family, others were traded for with other families, and many were featured in the film and TV series Bones of Crows.

“It's all about changing people's perspectives, widening their perspective and their mind. I find the best way to do that is just to teach people and to show people something really beautiful. Show them beautiful art and give them ideas about how they can incorporate it. So that was the whole point of putting on the display.”

From right to left: Instructors Carmen Thompson and Doreen Manuel with their Teaching Assistants.

The course included analysis of Indigenous representation in media. From white actors portraying Indigenous peoples, to a lack of regionality in how tribes are represented, the need for better representation is long overdue.

“Authenticity is really what I'm after,” says Doreen. “Watching all of these cowboy and Western movies, I have these cringe factors when I see certain things.”

“Indigenous people have been subjected to erasure for so long,” she says. “I taught Indigenous film history and show derogatory representation of Indigenous peoples in these movies, but also I point out absenteeism. Of the thousands of Westerns that were made, the majority of them don't even show Indigenous people.”

APPRECIATING AND SUPPORTING INDIGENOUS ARTISTS

Anyone who has spent years dedicated to honing the skills of a craft can appreciate the work that goes into mastering a craft. 891 Costume Department members, dedicated to mastering their own craft, felt a special deep appreciation for the works on display.

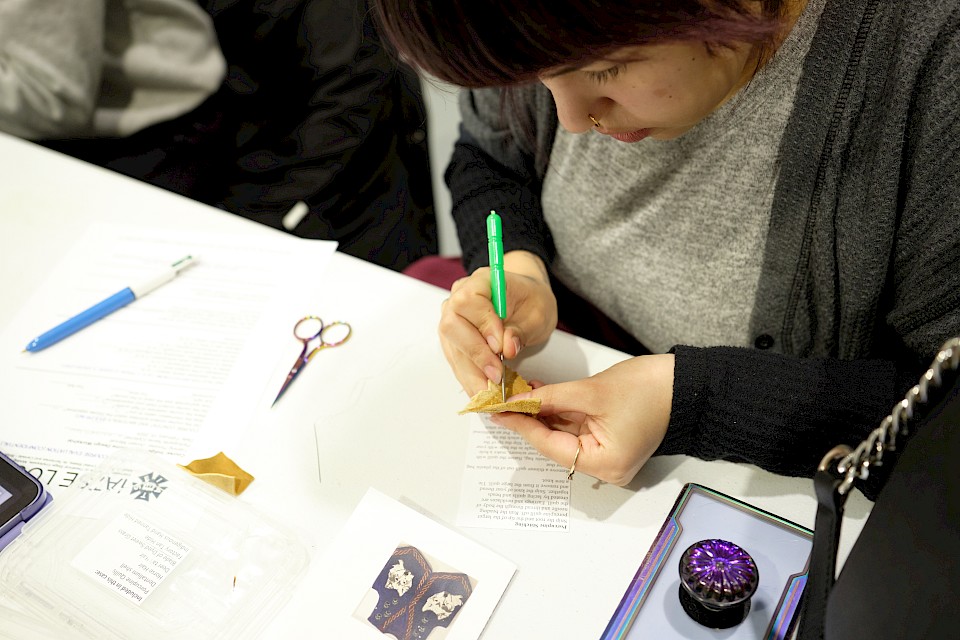

The course, held at the Union’s training centre at 1622 Boundary Rd., also provided participants with hands-on learning, with live demonstrations and over-the-shoulder direction from instructors on how to practice the skill of porcupine quill stitching.

Doreen brought in 30 pieces of buckskin and prepped quills so everyone could have their own little package of materials to work with. Beadwork, Doreen notes, started after contact and can be challenging to pick up as it requires good eyesight and dexterity. She felt that quill work, on the other hand, would be a unique experience.

“I told them that I'm not teaching you how to do this so that you can appropriate our culture – I’m teaching you how to do this because I want you to have an appreciation that it is art. That there is a definite skill involved in this,” says Doreen.

“I want you to know about something that we've been doing since before contact. Not so you can appropriate it, but so you can appreciate it, and will support Indigenous artists and help us build an economy where poverty currently exists.”

891 members who attended the workshop afterwards called the course “eye opening” and “enlightening.” Many expressed awe at the “beautiful display of regalia” and gratitude for the way the course fostered “cultural appreciation and respect.”

The mix of historical context and personal stories, and the invitation to feel raw materials and partially assembled garments, left a lasting impression on participants.

“I appreciated and enjoyed the personal anecdotes, and hearing about Indigenous film experiences,” said Ariana Preece.

“I appreciated all aspects of the course. Thank you,” said Nicola Ryall.

“Would love to see and hear more of this type of presentation,” said one Union member. “Wonderful course. More like this please!” said another.

Knowledge of authentic Indigenous artwork can empower artists and build respect and appreciation for the skills and perspectives Indigenous peoples bring.

One of Doreen’s motivations is to educate people about regional differences between tribes through showcasing various styles and designs that each have unique cultural and spiritual significance and were traditionally used to identify where a person was from.

“I showed them a wide collection of moccasins,” says Doreen. “I showed them the difference between them and I had the tribe name underneath the moccasins … I wanted them to understand that that's how we could recognize each other and where we are from.”

Doreen’s grandmother had her own style of flowers, for example. Today, when Doreen wears something that has the pattern of her grandmother’s flowers, people recognize them and know her lineage.

“My grandmother had a specific type of flowers that she beaded, and in fact, I was at a gathering one time wearing a dress that I had made for myself that had my grandmother's flowers on it, and I walked past somebody and they said, ‘Oh Mary Paul's flowers!’”

“After I got out of residential school, she was teaching me beading, and when I got to a certain point, she gave me this little container and it had all of her patterns and designs in miniature form. I still have that when I go to bead her flowers.”

CREATING PATHWAYS OUT OF POVERTY

Doreen’s dedication to beadwork and sharing knowledge and insight about her culture became an empowering force for her in her journey of finding ways to thrive after trauma. Canada’s residential school system, which was set up to try and erase Indigenous culture, left a legacy of inter-generational trauma that Doreen is personally familiar with.

“My mother, when she got out of residential school, was sent to live with her grandparents and her grandparents said to her, ‘What did you learn in that school?’ And she said, ‘I know a little bit of writing and reading, and I know how to cook a little bit and work in the garden a little bit.’ And they said, ‘So you basically know nothing about being a Ktunaxa woman. You're going to stay here until you learn everything about being a Ktunaxa woman.’ And so she did.”

“So when I got out of residential school, I feel like she was doing the same thing to me. She sent me to live with my grandma, and my grandma would barely speak English to me. So I had to hear our language and get a feeling for the language and start to learn really quickly what different words meant.”

“So I fell into the art of beading through my grandmother teaching me, and my mother told me, ‘Someday this is going to feed you and your children,’ because we as Indigenous people cannot always just rely on the non-Indigenous world to feed us.”

Before art and teaching, Doreen worked for years in intergenerational grief and childhood trauma counseling, developing programs for health and wellness for Indigenous peoples.

“My dad used to always say, ‘Choose something where you can help our people.’ Doesn't matter if you're a mechanic or a teacher, or a doctor or a lawyer, as long as part of your skills you can apply to helping our people.”

Grief and trauma counselling led to burnout, but she was determined to find another way to help people. She decided to get an MFA in film from the University of British Columbia, inspired by how powerful a tool filmmaking could be for Indigenous peoples to tell their own stories.

Now, she wants to see the film industry do more to build collaborative relationships with Indigenous peoples and open pathways that can help address ongoing poverty.

“One of my goals with all of the things that I'm working on is to help raise my people out of poverty and give them an opportunity to know the privilege that everybody else has been living by, and to know the privilege of being involved in the film industry.”

“We talk about reconciliation. Well, it has to include helping Indigenous people get out of poverty.”

Doreen is working on building a catalogue of Indigenous clothing items that could be rented out by the industry. Such an endeavour involves getting items insured and developing culturally appropriate protocols for how items are stored, cared for, and used in filming.

“The amount of funds that I made renting this collection to Bones of Crows was substantial for me. I was able to pay off my van. I make a decent income teaching at Capilano University, but I live in one of the most expensive cities in Canada. I'm imagining people living on the reservation with less opportunity to make an income where they live and how much the industry could help them.”

“There is really depressive poverty that some of our people live under, and it has everything to do with residential schools. You know when we're dealing with post-traumatic stress and inter-generational traumas, it's really difficult to get an education. It's really difficult to get off the reservation, and to think entrepreneurial.”

Her goal is to ensure Indigenous peoples who rent items to productions are fairly compensated, and that there is a pathway for participation in how Indigenous peoples are represented in film. Having the industry actively help fund the development of such a catalogue, and take more concrete steps to build collaborative relationships, would be a positive step, she says, towards reconciliation.

KNOWING THE BEAUTY OF WHO WE ARE

Doreen’s most recent artwork involves beading on canvas sneakers. She wants people to recognize that Indigenous art is alive, continues to thrive, and can be a voice for important conversations.

“I'm working on a collection of solid beaded Converse runners and on the outside of them I have sayings like ‘No More Murdered and Missing Women’ or ‘215’ in reference to the children's bodies that were found at the residential school in Kamloops, and on the inside are my grandmother's flowers.”

“I call it statement art. I want to do an exhibit at some point, and I would love to see them in a movie someday, just to start showing that we are not stuck in teepees in the old days. Our art is evolving the same way as any art form.”

With films and TV series being filmed all across Canada, Doreen sees great potential for Indigenous artists, and Indigenous peoples who own traditional and contemporary collections, to be more actively invited into the economic and cultural benefits of the motion picture industry.

“Prop and costume companies don't have large Indigenous collections. What they do have is limited and not very nice. It's been created by costume designers who didn't know our style and our art.”

“Our clothing is beautiful, and it takes a lot of artwork to create it. What I would prefer to see them do is rent from people like me who have these large collections, and there are people like me all across Canada who have collections my size and even greater.”

“My other hope is that we would turn to Indigenous designers to create new works.”

Pathways for creative collaboration and deeper learning are needed, she says. Taking courses that offer insight into the experiences and culture of Indigenous peoples is, in her view, an important step towards reconciliation.

“Reconciliation starts with truth,” says Doreen. “They're learning the truth when they take courses like mine. When they take courses about equity, inclusion and accepting diversification into hiring practices, they are facing the truth — the truth that we were subjected to genocide and we still are, until the effects of residential school are addressed in a way that is helping us heal from the pain and suffering we were subjected to.”

“Truth needs to be faced first. Part of that is learning the truth about who we are, looking at the beauty of what we wear. Knowing the beauty of who we are — that's some of the truth. It doesn't have to be all about the trauma, always. You do need to know trauma existed, but until you accept and look at what we wear, and what is part of our life, and how we traditionally raised our children, and our medicines, and our value in this world, everything we've contributed, you're not facing the truth.”

Written by Claudia Goodine

Photography by David Dolsen

To learn more about Doreen Manuel’s personal history and how it informs the work she does today, read “Her sacred ground: Doreen Manuel as defender of a legacy” published in Here Magazine.

Special thanks to Doreen Manuel and Carmen Thompson for leading the Indigenous Costume Design workshop, and to IATSE 891 Business Representative Crystal Braunwarth, Assistant Business Representative Jennifer McNeil, and the 891 Training Department for their help coordinating the opportunity for 891 members. Interested in learning about similar workshops for 891 members in the future or have questions about IATSE 891’s work on reconciliation, equity, diversity and inclusion? Email abr@iatse.com.